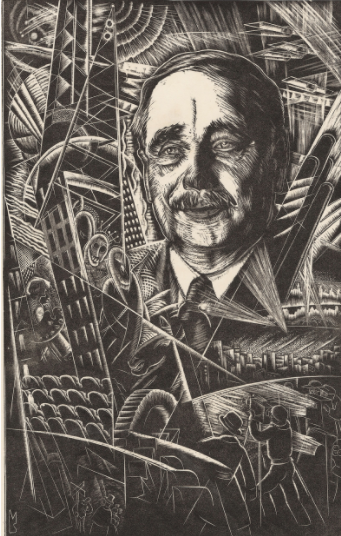

Maya Jasanoff Reviews, Sarah Cole's new book: Inventing Tomorrow: H.G. Wells and the Twentieth Century for The New York Review.

Would anything about this strange moment have surprised H.G. Wells? He was called “the man who invented tomorrow” because he seemed to have the future figured out. From his pages tumbled forth ideas for the air conditioner, the television, and the Internet, for servantless households, for mixed hot-and-cold taps—and for the arsenal of modern warfare. He anticipated aerial combat before there were airplanes and was credited by Winston Churchill with dreaming up the concept of the tank. In his 1914 novel The World Set Free, he described the detonation of an “atomic bomb.”

Today he remains best known for the explosively inventive novels that he lobbed over the threshold of the twentieth century: The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). But these titles marked just the beginning of an extraordinarily prolific and diverse career, which turned Wells into one of the most influential and widely read writers in the world. From 1895 until his death in 1946, Wells produced a book a year, if not two or three: science fiction and science textbooks, social novels and social history, scripts for movies and for political programs. Intellectually omnivorous, insatiably curious, boundlessly energetic, Wells had, as one interviewer wrote, a seemingly “infinite capacity for being interested”—and he aspired to cram every last bit of his learning into his writing.

David Lodge cheekily entitled his 2011 novel about the notoriously priapic Wells A Man of Parts, but Wells was nothing if not a man of everything—and, it seemed, everyone. “Thinking people who were born about the beginning of this century are in some sense Wells’s own creation,” wrote George Orwell, describing how Wells’s visions of the future indelibly stamped the imagination of his generation. “The minds of us all…would be perceptibly different if Wells had never existed.”

One reason for Wells’s enduring impact is that—like his predecessor Jules Verne—he managed, against the odds, to get so many inventions right. But his rarer gift was creative insight into the social ramifications of invention, making him as much a pioneer of speculative fiction as of science fiction (or “scientific romances,” as they were called then). Whereas Verne, for instance, championed new technologies as instruments of progress, Wells recognized that one couldn’t always trust science (let alone scientists) to advance the social good. Other fin de siècle authors wrote of impending world wars, but it was Wells who foresaw the devastating effects that twentieth-century “total war” would have on civilians. Beyond dreaming up tanks, mixed taps, and TVs, he gestured toward a world order shaped by genetic modification, surveillance capitalism, and climate change.

Wells never wrote a pandemic novel. Pandemics didn’t require inventing, after all—especially not by somebody who lived through the influenza of 1918–1919. Yet Wells’s multifarious portrayals of humankind as both beneficiary and victim of biological, technological, and environmental forces make him an uncanny reading companion during the coronavirus pandemic. In a landmark new study of Wells, Sarah Cole, a literature professor and dean of the humanities at Columbia, reveals a writer whose twin obsessions with biology and history saturated his sense of humankind and its future prospects. Inventing Tomorrow restores Wells to his erstwhile centrality in the intellectual culture of the early twentieth century and unspools a “mix of attractive and repellent” ideas that resonate in an ambitious, anxious twenty-first.