Derek Penslar, William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History at Harvard University, has long studied modern Jewish history from a global perspective. In his new biography of Theodor Herzl, Penslar, resident faculty at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, examined how the founder of modern Zionism’s personal life influenced his political impact. He discussed Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader (Yale University Press, 2020) by phone from Toronto.

Q: Your new biography, Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader, focuses on how Herzl’s personal crises as much as broader anti-Semitism propelled him into a leadership role. Do you believe this is particular to Herzl and Zionism, or do you see this as a larger pattern, particularly for charismatic leaders?

Penslar: I think this is true for great political leaders across the board, in particular leaders of nationalist movements or anti-colonial movements.

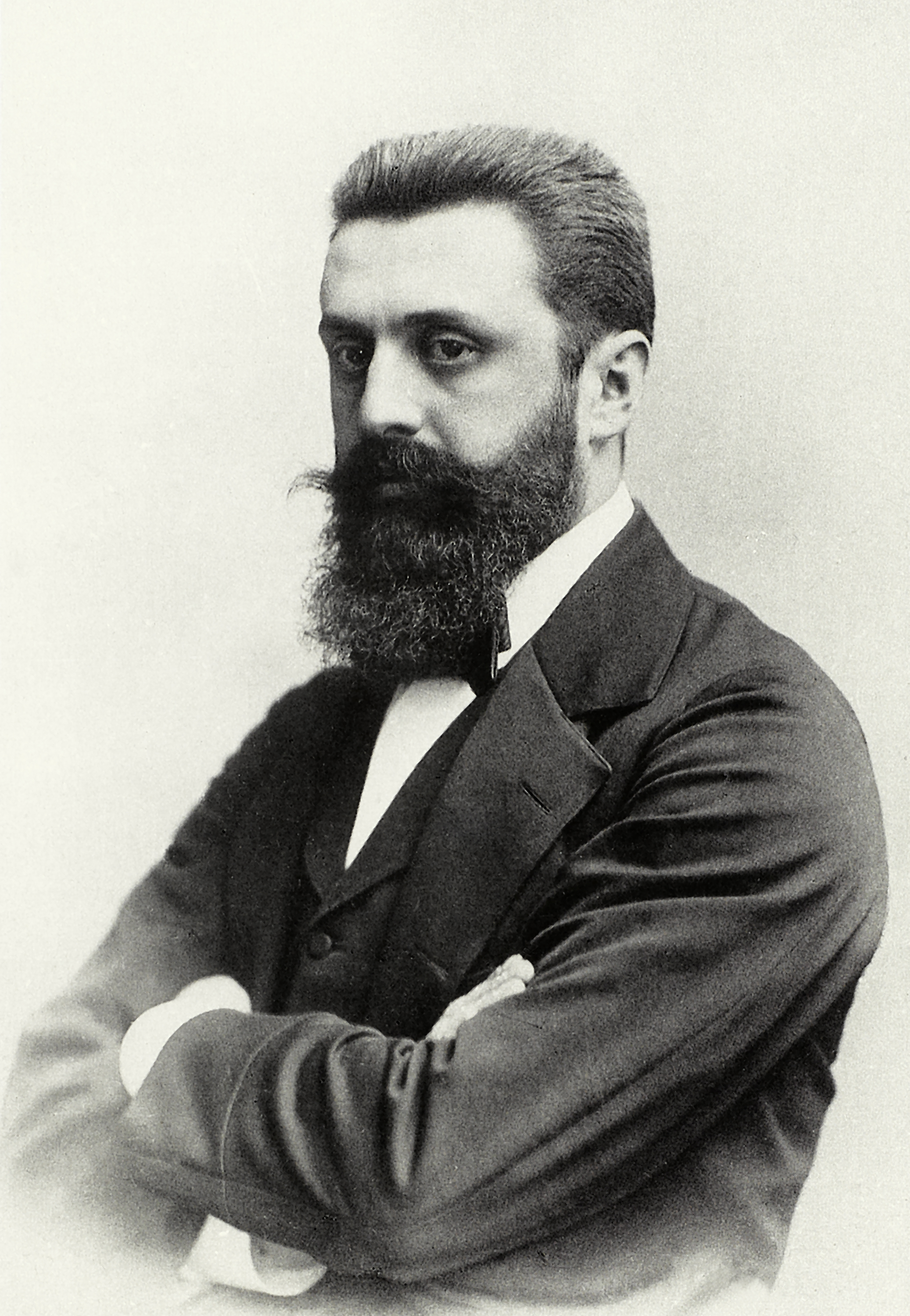

One of the main arguments in the book is that charisma is dialogic. What made Herzl a great leader was a combination of his own internal drives and the fact that he was the right man in the right place at the right time. Charisma means nothing if there’s no one to be charismatic for – the charismatic is defined by their audience. At the fin de siècle, there was a certain type of European Jew who was looking for a great leader, someone to inspire them. There was a Jewish national idea in the air. And then along came Herzl. He very much was the right man in the right place at the right time, who also had qualities of genius and leadership. And it didn’t hurt that he was a strikingly handsome man with a nice beard.

– Derek Penslar

Although Herzl was raised in comfortable circumstances in Budapest, he fabricated a more dramatic family history to his first biographer, giving his Eastern European family a higher-status history as converts under the Spanish Inquisition. Would you discuss this in terms of his capacity for re-invention and elaborate on how this shaped the leader he became?

Penslar: It certainly is typical of Herzl to invent a more colorful past, but it was not uncommon in his era for Jews of Ashkenazi [Eastern European] origin to try to tie themselves to the Sephardic [Spanish or Portuguese] past because it was associated with distinction, with a kind of Jewish royalty. Ashkanazim often believed in Sephardic superiority. There are, even to this day, Jews with quintessentially Ashkenazic backgrounds who insist that a certain branch of their family is Sephardic. It’s seen as exotic and ennobling.

Herzl identified with the Prussian nobility and tried several times to join the military. Would you discuss how this failure to assimilate as he’d hoped led to his search for an alternative?

Penslar: There is a critique of Zionism that Zionism is the ultimate form of assimilation because it presents Jews as a nation, like other nations, and claims Jews must have a homeland as other nations have a homeland and have a national language as other people have national languages. This goal of turning Jews into “normal” people is a form of assimilation. There are ultra-Orthodox Jews who to this day say that the state of Israel is essentially a carbon copy of a gentile state. Herzl’s Zionism does reflect, in a way, the desire to be a good European. He envisions a state where people will speak European languages and consume European culture. Even when he becomes a Zionist, there’s a part of him that is still connected with the goal of assimilation.

You detail Herzl’s neuroses, drawing a picture of a needy and immature man. Would you talk about how he displaced these needs from his marriage and family to a larger stage?

Penslar: Herzl was very needy, overly attached to his parents, and rather narcissistic, and he could not find satisfaction in the role of husband. To be a good husband, to be a good spouse, you have to give of yourself, and you have to really be there for the other person. Also, Herzl couldn’t really be comfortable in the role of parent because, as we all know, parents sacrifice for their children. He was willing to sacrifice himself – but to a cause of his own making. He created the political Zionist movement. He was its center, and he felt empowered and adored. That’s very different from the humdrum pleasures of being a husband or a father.

Herzl found himself – and his voice – as a journalist in Paris. Would you elaborate on how this period shaped him or shaped his writing of his seminal work, The Jewish State?

Penslar: Herzl was a journalist through and through. Even as a teenager, when he started writing his first journalistic pieces, he was a master of description and quick analysis. He knows how to get his point across quickly, and he knows how to conjure up effective imagery. He was also very good at evoking emotion when he wrote about the working classes and the suffering of the poor. He wrote in a way that evoked feelings of compassion and pity. In the same way, in his Zionist writings, he eloquently expressed the needs of the Jewish people. His journalism trained him how to write an effective political manifesto.

Herzl’s conflicting feelings about Jewishness – vacillating on whether it was a religion or a race – seems to have led to his embrace of Zionism. Would you talk about this conflict and how Zionism resolved it?

Penslar: Even though he himself was not religiously observant and he knew that many Jews in his day were not religiously observant, Herzl still saw the Jewish religion as a unifying force. He wrote that what unites Jews might ultimately be a sense of ethnicity, but that it is often defined through religion. The religion is ultimately a bond, even if we’re not religious people. Herzl believed that Jews shared a common sense of relationship with the God of Israel. Herzl’s novel Altneuland about an ideal future Jewish homeland is peppered with references to God, although the homeland he envisions is entirely secular.

The story of Moses mattered a great deal to Herzl, largely because he thought he was a second Moses. He did not believe that Jews could be defined in racial terms because Jews from different parts of the world look so different. I think he was actually on to something about modern Jewish identity, which often flees from religion yet still relies on it.

How do you view the role of charismatic leaders like Herzl in our current crisis? Are they useful in rallying support or mass action, or do they distract from necessary actions or experts? Do you see any Herzl-like leaders emerging in this current crisis?

Penslar: You need charismatic leaders to get things started. An anti-colonial movement that’s trying to throw off colonial oppression needs a charismatic leader like Gandhi or, if you’re starting a national movement from scratch, like Herzl. Once you have a well-established state, you want competence. You want people like Angela Merkel or, with all due respect, Justin Trudeau, who has turned out to be a much better leader than I would’ve given him credit for.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Photo Credits: Theodor Herzl: Courtesy of David Matlow; Derek Penslar in Toronto, April 2020.