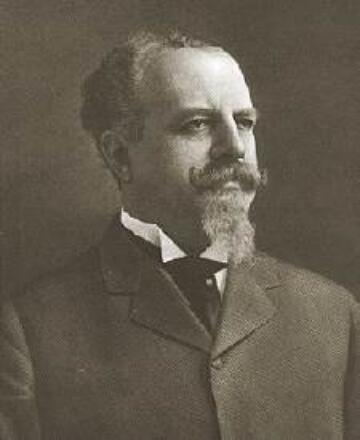

The push for such a museum began in the late 19th century and reflected the importance of Germany as an educational model for American universities. The chief proponent of the museum was a remarkable young scholar from Germany, Kuno Francke, who joined Harvard’s German department in 1884 and made it his mission to help Americans gain a better understanding of Germany’s cultural past. Beginning in 1897, Francke started campaigning for the creation of a Germanic museum that would embrace the cultures of Germany, Holland, Scandinavia, Switzerland, Australia and even England.

Adolphus Busch Hall

One of the most striking buildings on the Harvard University campus, Adolphus Busch Hall is remarkably fitting as the home for the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. The structure boasts an unusual history with roots in a historical anomaly – the establishment in 1901 of a Germanic Museum on the Harvard campus to highlight the achievements of Germanic culture and society.

Building understanding between two nations

Francke campaigned to create a Germanic museum at Harvard to help Americans better understand Germany's cultural past.

After exhaustive work by Francke, who won support from then-Harvard President Charles Eliot and even Kaiser Wilhelm II himself, the museum was established in the Rogers Gymnasium, which was repurposed as exhibition space. The new museum was opened to the public in 1901 and formally dedicated two years later. The space initially featured a collection of plaster-cast reproductions of German statues and art and photographs, largely donated by the Kaiser. Francke, however, set his sights on obtaining a more expansive facility that could serve as a “teaching museum” with artifacts and historical material spanning the centuries of German culture.

A Harvard committee was formed to raise funds for such a venture but it was largely the generous support of St. Louis brewer Adolphus Busch that allowed Harvard to secure a location and fund a design by the famed Dresden architect German Bestelmeyer. The building was constructed under the direction of Herbert Langford Warren, the founding dean of the Harvard School of Architecture.

What would be named Adolphus Busch Hall was erected in 1914-1916. The precast domes of the Kirkland Street entrance rotunda and what is now Charles Kuhn Hall required engineering techniques that had never been used before in the United States. At the time, based on the cost per cubic foot, it was the most expensive building built by Harvard.

The building’s exterior is dotted with sculptural and decorative flourishes and etched quotes from the likes of Kant, Goethe and Schiller. A small courtyard garden is graced with an imposing bronze lion, a copy of an 1166 monument erected by Henry the Lion at the Brunswick Cathedral in Brunswick, Germany.

Politics bring an uncertain future

Events in Europe, however, nearly derailed plans for turning this imposing structure into a Germanic museum. World War I initiated a period of fierce anti-German sentiment in the United States and the national Prohibition turned the public against brewers such as Busch. Despite the obstacles, the Germanic Museum opened to the public in April of 1921, with Francke, then retired from the Harvard faculty, as honorary curator.

More changes came, reflecting events in Europe: The museum was closed from 1942 to 1945 during World War II, when the U.S. Army occupied the building. It re-opened in 1946 and four years later, it was renamed the Busch-Reisinger Museum. Beginning in 1930, when Charles Kuhn was named curator, the museum shifted from an emphasis on showcasing reproductions to establishing an unusually fine and extensive collection of original art, primarily 20th century German expressionist paintings. In 1958, a D.A. Flentrop organ was installed and recitals and concerts were added to the museum’s programs.

Focus shifts to Europe with Center's move

In 1989, Harvard decided to relocate the Busch-Reisinger Museum and its now-splendid collection of German and central European Art to a new building to be erected behind the Fogg Museum. In 1991, the Busch-Reisinger Museum opened in Werner Otto Hall where it displayed significant works of Austrian Secession art, German expressionism, 1920s abstraction, and materials related to the Bauhaus as well as postwar and contemporary art from German-speaking Europe. Busch Hall continued to house the founding collection of plaster casts of medieval art.

Today, Busch Hall provides space for CES offices, classes and programs, while a section of the building has been preserved as a museum, and is administered by Harvard Art Museums, which also oversees the Busch-Reisinger Museum. Several CES professors also maintain offices in this section of the building.

In summer of 1989, CES moved into a newly renovated Busch Hall; the construction was supported by the generosity of Jean and Charles de Gunzburg, who also helped establish an endowment that would support maintenance of this historic building. The building was named after their mother Baroness Aileen (Minda) de Gunzburg.

Visitors can still get a sense of Francke’s original vision with a stroll through the Charles Kuhn Hall, which has been preserved as a showcase for the plaster casts and replicas that formed the nucleus of the original collection. This includes a dramatic replica of a 13th century church gate in Saxony, a replica of an intricately carved 13th century portal from a Freiberg church and original sandstone statues from the 18th century representing the four seasons. A series of provocative fresco paintings by Lewis Rubenstein, commissioned in 1935-36, depict the Norse legend of the “Twilight of the Gods,” but reference contemporary German history with a gas mask among the symbolic swords and armor. Free midday organ recitals are offered regularly.

The building continues to delight the campus with its architectural charm, including the sculpted faces around its exterior and the grand lion in its courtyard garden.

History of the Germanic Museum at Harvard University

More Information

- In Focus: Adolphus Busch Hall (Harvard Art Museums)

- Hidden spaces: Adolphus Busch Courtyard (Harvard Gazette)