To research schools in Germany, Stefan Beljean went to the source

As a CES Dissertation Research Fellow, Stefan Beljean spent 10 months in Berlin conducting fieldwork in German secondary schools. He spoke about his findings and the benefits of his strong connection to the Center.

How long have you been a student affiliate of the Center?

I’ve been an affiliate since I completed my coursework in my second year. My adviser, Michèle Lamont, is a faculty associate at the Center, and she encouraged me to apply. Other graduate students recommended it as well. It’s wonderful to have office space here, and you get to know people from different departments. That’s been great, and it helps broaden your perspective.

Tell us about your research and the fieldwork you conducted in Berlin.

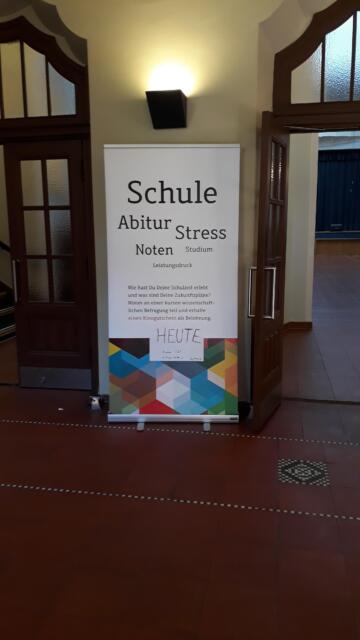

My research focuses on high school students. I’ve done some work here in Boston and in Berlin, working with secondary students at several schools. I’m looking at how students are preparing for or focusing on going to college during their high school experience. I found quite a contrast between the two countries.

In the U.S., especially for middle-class and upper-middle-class students, much of the high school experience is geared toward preparing for college. Students are focused on taking AP classes, doing the right extracurriculars. In Germany, there’s more of a disconnect between those two levels of education. The prospect of going to university is certainly there, but people don’t align their actions and orientation so much with it. In sociology we would say it has less of a “structuring effect” on the lives of secondary students. Their everyday lives aren’t entirely oriented toward going to the best possible college, whereas in the U.S., for students of the same socioeconomic class, that’s often the case.

Is the attitude toward extracurriculars the same in Germany as in the U.S.?

For most students it’s very different. The average German secondary student is more relaxed and has more of a life outside of school than the American students I’ve seen. But extracurriculars are also not as integrated into school life in Germany; they’re often based in the community or related to other organizations. School for American students can be a full-time job with academics and then all the activities, too.

So that’s true even for more-privileged students?

Yes. I found it interesting that in Berlin, students who come from a very similar social background — children of doctors or lawyers — had such a different attitude. You would think they’d be as keen as American students, facing pressure from their parents or vying for admission into competitive career fields. But instead, they say, “I would never give up my social life or sacrifice my weekends for school. I would not give up everything for it.”

There is a small group of students who are very ambitious and entrepreneurial in how they approach school. They want to go into fields that are very competitive, such as medicine and law. So certainly there’s an element of that competitiveness. But it’s not as common as with American students, many of whom are expected to go to university.

How does this relate to research on the achievement gap?

There’s a lot of interest in sociology on both sides of the achievement gap. We’re asking two questions: How do people get left behind, but also how do they stay ahead? The upper class and the upper-middle class have strategies to keep getting the best possible education to convert into the best possible jobs. How do parents invest in their children by sending them to all kinds of extracurricular activities, tutoring, etc.? My research acknowledges that, but I’ve made the shift to focusing on the students themselves and how they experience this pattern. Because adolescents at some point become independent beings and might resist their parents’ efforts. Not all of them — even the Americans — are these young careerists who try to reproduce the status of their parents. Some of them say instead, “I want to have balance in my life.”

Can you talk about the fieldwork experience in Berlin?

I do what is known as qualitative sociological research. I conduct interviews with students, and I also go on site at the schools to observe and participate in their lives. To do that, of course, you actually have to be there. You can’t just download a data set and try to understand what their life is like. You actually need to establish a relationship with the people running the school and build that trust so you can observe and nurture those relationships. Being in Berlin for months on end was critical for me.

I used my time in Berlin not only for actual research, but for understanding the German sociology of education. I spoke to a lot of scholars in Berlin, and they gave me great advice.

What will you focus on this year?

I’ve received a Dissertation Completion Fellowship through the Center for the coming year, so I will be doing a lot of writing. And I’ll be helping to organize the Social Exclusion and Inclusion Study Group at CES.